The Harmful Effects of Ageism on the Elderly

By Meredith Kimple

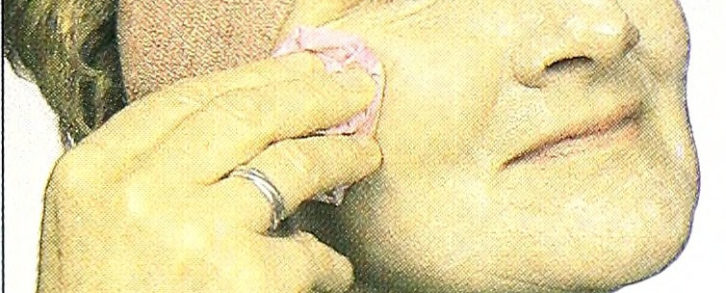

Ageism is discrimination or prejudice against individuals belonging to a certain age group, particularly the elderly population. In a previous blog post, we explored the importance of older individuals having a sense of purpose, especially since our culture worships at the altar of youth, physical fitness, competitive drive, and achievement. Because our culture highly values these aspects of the human experience, older individuals may feel that they no longer have a valuable role to play in society. Ageism promotes the idea that growing old, while certainly preferable to an early death, is a truly terrible process that should be resisted at all costs. In fact, the fear of aging is used to hawk countless wrinkle-reducing skin creams, hair dyes, and plastic surgery procedures to the masses, as the prospect of facing the physical changes associated with aging is met with collective distaste.

Though there have been more positive portrayals of old age in commercials and various other forms of entertainment in recent years, this long-held, widespread rejection of the elderly is not to be easily uprooted. As the Baby Boomer generation ages, a significant portion of our population is attaining elder status, and while this change in demographic may help combat negative perceptions of old age, the harmful effects of ageism on our senior loved ones are of a significance that warrants our immediate attention.

Ageism in the healthcare community is surprisingly prevalent, often to the detriment of older patients’ health outcomes. Doctors may either overestimate or underestimate the medical concerns of their older patients, with no conscious effort to do harm. Certain conditions or pain may be dismissed simply because a patient has reached an advanced age; on the other hand, some doctors overprescribe medication or order rigorous examinations and tests primarily due to a patient’s advanced age. In both cases, some medical professionals make decisions based on the age of their patient and the general assumptions that age gives rise to, rather than on the individual patient’s actual physical condition and medical needs. Doctors may unintentionally patronize and talk down to their older patients in an attempt to communicate effectively, mistakenly assuming that these individuals suffer from hearing loss or cognitive impairment. They may also carry preconceived notions about the health issues seniors encounter while dismissing others that do not fit their understanding, such as those relating to sexual intercourse. If you accompany a senior loved one to doctors’ visits, allow them to answer and ask questions as much as possible while speaking to their physician; some doctors address the friend or relative rather than their patient when explaining various test results or procedures, which removes agency from the older patient.

But of perhaps greater significance is the toll ageism takes on our older loved one’s self-concept and esteem. In the past, we’ve discussed the emotional impact aging has on a person; the loss of various physical abilities, cognitive decline, depression, isolation, and numerous other changes can chip away at even the healthiest self-image. Ageism compounds these problems by socially reinforcing the idea that growing old is a terrible experience, rather than one that is as rewarding as it is challenging. Older people have been conditioned since childhood to view aging as an unfortunate consequence of survival, or as a sort of “half” existence that shakily straddles the fence between life and death.

Those of us who have older loved ones know that the reality is far different. While the elderly often find participating in communal activities and staying engaged a bit more challenging than their younger counterparts, many older individuals continue to lead active lives. They volunteer their time and talents, attend church services and classes, join clubs, eat meals with friends, support the arts, watch sporting events, and continue to pursue their favorite hobbies. When our society callously reduces the vibrant, active seniors we know and love to a pastiche of cruel and cartoonish stereotypes, it attacks their right to enjoy their later years. They have been bombarded their whole lives with unflattering portrayals of aging, and have internalized the notion that their bodies are broken and useless, and their lives no longer have value. This negative self-perception is bad enough on its own, but when it leads older individuals to believe that certain serious symptoms and pains are simply a normal part of aging, they may not report them to their primary physician, putting their lives in jeopardy. Additionally, if an older individual has a low opinion of themselves, it can put them at greater risk of mortality when battling illness and recovering from surgery; a positive self-image plays a pivotal role in a senior’s physical health and stamina, and therefore, it is imperative to foster and nurture our older loved one’s self-esteem. There is even evidence to suggest that the more optimistic an older individual is about aging, the healthier and younger they feel.

So what can we do to combat ageism?

Because ageism is so entrenched in our culture and will likely take quite a while to even partially eradicate, the changes we can make will have to be on a smaller scale. Start with yourself; treat older individuals you encounter with respect, and notice when you make snap judgments about their functioning based on their age or how frail they appear. Avoid making assumptions about their level of comprehension, and do not talk down to them or behave in a condescending way. Some seniors genuinely may need you to speak loudly or repeat yourself, but do not do so unless prompted by an older person. Refrain from making disparaging comments about old age, and approach your own aging with optimism and energy. Speak up if you witness hostility or blatant discrimination towards an older individual.

If you hear your older loved one making negative comments about themselves or putting themselves down over their advanced age, remind them of all the good aspects of their lives. Aging can be frustrating physically, socially, and emotionally, and even the most self-assured person is subjected to bouts of hopelessness and anger at the changes it brings. As their loved ones, we should be encouraging and empathetic in these difficult moments; we should do whatever we can to focus our older loved ones’ energies in a more positive direction. If you notice that they are down or in despair for a prolonged period of time, talk with them about speaking to a licensed counselor. Kind words are not always enough to end deeply internalized ageism, but our support for the elderly and efforts to monitor our own thinking can bring meaningful changes to our society’s current view of aging.